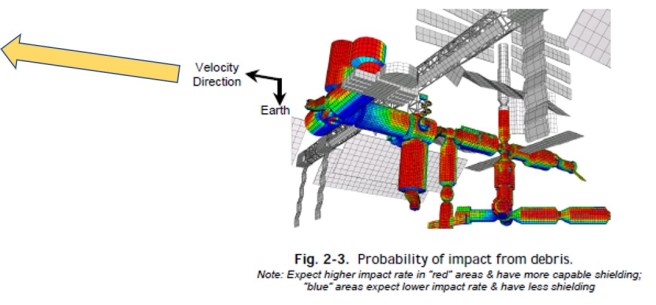

There is an oddity to the International Space Station, its name – a station. On Earth this would be fine, a station, as in stationary, not moving. In space, though, “station” is a bit of a misnomer for a facility going once around the Earth every 90 minutes and traveling 15,500 miles per hour. Pictures, even videos of spacecraft coming and going from the ISS, cannot do justice to its movement as it traces its orbital path. With that stationary bias, as if the ISS merely floats in space above us, it’s also lost that the space station has a front. The forward Unity, Kibo and Columbus modules take the micrometeoroid hits along the way. Everything facing forward gets the dings. Unfortunately, adding a figurehead or feature to the ISS to clearly show it is a ship traveling in the sea of space above Earth and where the front is would be out of the question. An ISS figurehead at the bow would block the front door and the mating adapter where spacecraft dock to deliver cargo and crew.

Similarly little appreciated is how NASA once upon a time had a plan to complete the ISS and soon after ditch it in the ocean. The ISS would have been built over decades to be operated for only five years. In a world of NASA projects that last a career, this qualifies as a blink of an eye. This massive and international project, the only reason to keep flying the Space Shuttle after the loss of Columbia, would be completed in 2010 and de-orbited in 2015. The flirtation with the idea of building the ISS and soon after destroying it was (fortunately) brief – a span of a few years, ending with acceptance of the absurdity of such a plan. I had the unique privilege in 2008 of briefing NASA leadership about the big picture for exploration, the ISS and everything else in the NASA budget, and declaring this end-of-life plan for ISS ridiculous (only in more diplomatic terms, with pretty graphs, and many budget scenarios and lots of numbers). As evenly as I was told I presented, this was a time when pointing out this apparent defect in planning was still a formula for an unexpectedly heated immune response (and not being invited back). We’ve been given our orders, which is what we plan around. Period. Until new orders.

It’s now 2021, and the ISS is still going strong. Current ISS planning looks as far as 2028, officially anyway, but practically, the ISS is part of NASA for the foreseeable future. In all this, a question repeatedly arises – what is the cost of the ISS per year? In 2010, the slight nuance to this question from on high was “What does it cost for NASA to own a space station,” likely from a suspicion something was off about the other form of the question. The “owning” angle would not be better for questioning the station’s yearly costs. Most answers to the ISS yearly cost question are “not even wrong” for many reasons. However, looking at the ISS books shows this also applies to the question. After years of being fortunate to be involved in uncomfortable questions, it became clear that asking the right questions is much more important than answers to poor questions.

Wrong questions, good questions and a trip down a rabbit hole

What might motivate questions about the ISS annual costs? A frequent, if not as advertised, reason is the belief that the question leads to a number that is the same as the amount of NASA funding freed up for other distinct projects should the ISS end. This is Deja-vu all over again, like the time over a decade ago when NASA planning called for building the ISS and then, not long after, hurling it into the Pacific. Today, the part about de-orbiting so soon is gone, but the notion that a NASA lunar program receives all the freed-up ISS funds for wholly new projects remains. This would help get those Moon plans to add up. Here again, the dull notion raises its head – that ISS funds, when ISS ends, are funds freed up to be used as down payments for a lunar lander, an outpost, or a giant rocket. And again, we have a question that is “not even wrong.”

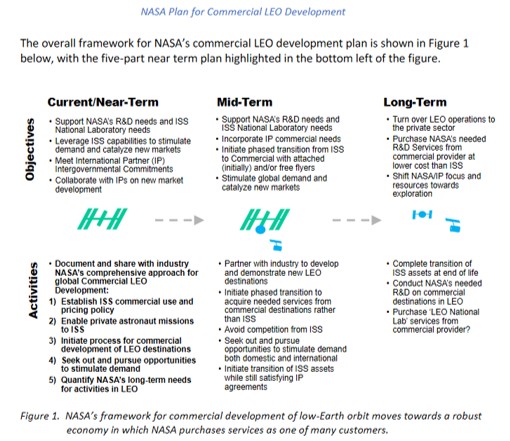

There is an excellent reason to ask some form of the question about the yearly cost of the ISS – a vision that someday, NASA will buy time and space for its astronauts on private space stations. Even better, NASA will be one of many power, air, food, water, ports, and space customers at those private stations. NASA would not own the lab, but it would rent the space like a room at the Hampton Inn. This is an entirely different reason for understanding the cost of the ISS per year. It is all about business cases that need to know where we are to understand what we must improve. NASA now runs with a business case for getting cargo to the ISS, the ride, not by using the entirely owned and operated Space Shuttle, but by hailing a cab. This became the US ISS Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program or “COTS.” The business case then began with measurable NASA’s needs – tonnage to the ISS per year, preferably at a lower yearly budget than continuing to use the Space Shuttle and its logistics module. Similarly, asking about ISS costs sets the stage for an excellent question. How might private space stations be had, where NASA rents rather than owns, for less yearly budget while also growing capabilities?

Entertaining a cost question about a NASA project gives new meaning to “going down a rabbit hole.” In the ISS case, what will not be found down that hole is an answer equal to funding one day freed up for just anywhere else. There are three legs to this stool, most of which, by dollar amount, do not have to do with operating the ISS.

The first cost is basic “research” about humans in space, a body of knowledge unlikely to be declared complete anytime soon. This is what is done on the ISS, not the cost of running it. In the 2021 NASA budget, this is about $350M a year.

A second cost usually attributed to ISS is the cost of getting there. When asked about running a lab, the standard answer is to add the flight cost, supplies, and the rental car to get there. This is $1.7 billion a year in 2021.

Third is the “ISS Systems Operations and Maintenance,” the actual cost to run the station at about $1 billion annually. This is how anyone googling ends up with a reply to the “cost of ISS per year” of “$3 to $4 billion a year” (also here). This is the sum of these three parts. It’s in diving into these three parts that it’s easy to realize the confusion afoot.

Going further down the rabbit hole Alice?

Dissecting is a good word for looking deeper into ISS costs, as this will get messy. For one, NASA will unlikely cease its R&D into humans in space. If NASA moved to a private station, the thought might be equivalent research could be done for less, but just as well it might invest more by choice. NASA could finally dedicate more resources to results and less to the means of getting these. Tossing these comparisons into spreadsheet territory would distinguish NASA astronauts from others (international partners) and then only do research, minus the effort to keep things humming along. The private space station equivalent research is not seven astronauts. But is it two, five, or in between? In cost circles, when confronted by valid but competing reasons why a cost might go up or down a first good guess is it will probably not change much at all.

Similarly, doing the research needs astronauts, and NASA currently manages to get its cargo and crew to the ISS commercially. A private station might do better if also tasked with the ride, now a shuttle bus to the hotel. Still, it could arguably be unlikely to do much better given that NASA has already acquires these services in a very competitive field (Northrop Grumman and SpaceX, with others to come). Current post-ISS thinking already recognizes this – the transport to the ISS is being commercialized, and transport to a private station would not be re-commercialized. Any changes here will result from how costs are attributed to non-NASA crew and cargo – employees of the private station. (As well, showing more morphing than transformation, future transport of cargo and crew would remain funds for transport of cargo and crew, just to the Moon.)

After the research and the transportation to a space station, the last element, which seems to be the ISS yearly operational cost ($1 billion a year), requires a secret decoder ring that comes from years of experience asking where the bodies are buried. However, anyone who dares go down that rabbit hole will discover that even that question is not valid. The better question is *how are the bodies buried, where, and why.* The number here gets clearer when realizing that NASA budgets for space exploration have always included Kennedy Space Center’s expected and necessary ground and launch operations for when the day comes to prepare and launch deep space missions. Yet, the budget has been missing when looking at these same budgets for the expected and necessary mission and flight operations at Johnson Space Center.

This is part artifice and part policy. As long as NASA is in the crewed space exploration business, many of these human spaceflight costs are attributed to whoever the current customers are – or now the remaining customer – the ISS. When the Space Shuttle ended, a look at the NASA budget clearly shows this institutional effect. The Space Flight Support budget shot up, and many people and organizations from Shuttle moved there. These people (and the dollars) were not freed up for new hardware with the Shittle ending. (The similar effect here for when the ISS ends significantly affects the possible budget advantage should NASA move its research to a commercial station.)

Are you confused yet? Searching for better questions.

If all this seems to say, the operation of the ISS is nearly free to NASA, apart from getting there and actually using it to do research, it’s not. It does mean the commonly googled number of about $3 to $4 billion annually for ISS costs is misleading. This is a gross error if you think this ISS yearly dollar number equals the dollars usable for other project possibilities when the ISS ends.

Rather than abandoning our rear on our way to deep space, the question is how to strengthen it so the deep space voyages are possible.

Yet a poor question has its uses – it can lead to better questions.

What might NASA do in a permanent place (or places) in LEO as an anchor tenant, renting a room or rooms but not owning the hotel and lab or part of an international one? Aside from doing the numbers on a business case for NASA (and another one for the private partner finding non-NASA customers), might we see NASA do even more in orbit for the same yearly ISS funding? If doing more, what more? With byzantine accounting, the benefits we should focus on are too easily lost in the fray. Rather than abandoning our rear on our way to deep space, the question is how to strengthen it so that deep space voyages are possible. If we are to have orbitals one day, a long string of pearls from Earth to the sky above and beyond, these are the right questions.

Also see:

From the before times:

- Market Analysis of a Privately Owned and Operated Space Station, Crane, Corbin, Lal et al, 2017

- Survey shows ‘hundreds of impacts’ on ESA’s Columbus module Spaceflightinsider.com, with an excellent video clip of the ISS direction of motion, February 8, 2019

- NASA Plan for Commercial LEO development, June 7, 2019

- NASA selects Axiom Space to build commercial space station module, SpaceNews.com, January 28, 2020

- SpaceX has won a big NASA contract to fly cargo to the Moon, Eric Berger at Ars Technica, March 27, 2020

More recently:

- The Ugly Bargain Behind NASA’s SLS Rocket, Supercluster.com, January 26, 2021

- NASA Commercial LEO Destinations Industry Briefing, March 23, 2021

- NASA to offer funding for initial studies of commercial space stations, SpaceNews.com, March 23, 2021

“NASA, though, did reveal its projected demand for commercial space stations at the briefing. It estimates it will need two astronauts on orbit continuously, performing 200 investigations a year. That is significantly below the current use of the ISS, which has seven people on board.”

Notice the potential error in this comparison, as not all astronauts on the ISS are NASA (the others being from Canada, Russia, Japan, and Europe), and much of the crew’s time is not available for investigations, being caught up in maintaining the ISS. For a private station, maintenance and operations should be the responsibility of the private station (non-NASA crew).

- NASA wants companies to develop and build new space stations, with up to $400 million up for grabs, March 27, 2021 re. the Commercial LEO Destinations project

Notice the error again: “The International Space Station costs NASA about $4 billion a year to operate.” If pondered momentarily, the NASA statements in the same piece say otherwise.

It’s fascinating how much thought goes into planning and maintaining such an incredible structure in orbit.

LikeLike