Before “commercial space,” there was “cost-plus space.” In this Byzantine world, whistle-blower Ernie Fitzgerald said in the 1960s, “There are only two phases of a program. The first is ‘It’s too early to tell.’ The second, ‘It’s too late to stop.’” While today’s trending topics in space exploration are about going commercial, not cost-plus, Starships and Starlink, space tourism, billionaires, and SPACs, it is worth remembering how any project can go askew. Knowing what to avoid, space exploration can finally be more about planets and less about plans.

If space exploration projects were territory, a look at recent projects would show that commercial contracting has been seizing ground once exclusively reserved for cost-plus contracts. In 2018, NASA selected nine companies to get payloads to the surface of the Moon on a commercial basis. The following year, NASA signed a firm-fixed-price contract for the first part of a lunar Gateway, a space station in lunar orbit. With the partner retaining ownership of the element, NASA went commercial again. Last year, NASA awarded a contract to get cargo to the Moon as a commercial delivery service, the same way it contracts to get cargo to the International Space Station. Then, this year, NASA awarded a contract for a lunar lander for crew, the SpaceX Starship, also firm-fixed-price, with payments by milestones. Payment for milestones (read: results) is also very commercial.

Recent NASA Commercial Contracting

- NASA Commercial Lunar Payload Services

- NASA Gateway Power and Propulsion Element

- NASA Gateway Logistics Services

- NASA Human Lander System

- More on these programs

The idea seems simple. Any plan will have many moving parts if you want to explore the solar system. If there were more focus on results, as with commercial contracting, there is a greater chance you avoid each part having just Fitzgerald’s two phases. Uncertainty about where you are heading and no steering or brakes has proven to be a dangerous mix. Traditional “cost-plus” space did this mix predictably often.

On the other hand, for NASA to get cargo to the ISS, a commercial approach showed how to do more with less. There is still uncertainty, especially as cost risk shifts to the private sector partner. This makes for a proper and more common-sense alignment of everyone’s incentives, public and private. We sink or swim together. However, the steering and brakes definitely work, as funds are paid out for progress, not activity, and NASA is freer to put on the brakes for one partner, knowing they still have a backup partner. But much of this logic goes beyond just the word “commercial.” If cost-plus projects seemed at times like paying to cut grass by the hour (cutting the grass is gonna take…a long time), and commercial contracting is an improvement, might there still be pitfalls ahead akin to Fitzgerald’s two program phases?

Revisiting commercial ingredients

Budget realities are close behind the laws of physics. Plans for space exploration learn this the hard way. Space exploration plans that are entirely government-led and owned have discovered that sticker shock can stop a grand plan just as much as rocket equations that don’t add up. Commercial programs would seem a way out of this trap, costing less and fitting within the prospects of steady budgets, maybe even growing a little year over year but not going up generously. In either case, even when budgets are better, projects that span a career must ask if the good times will last. Again, commercial programs at more modest costs would seem better built for when budget growth is modest as well.

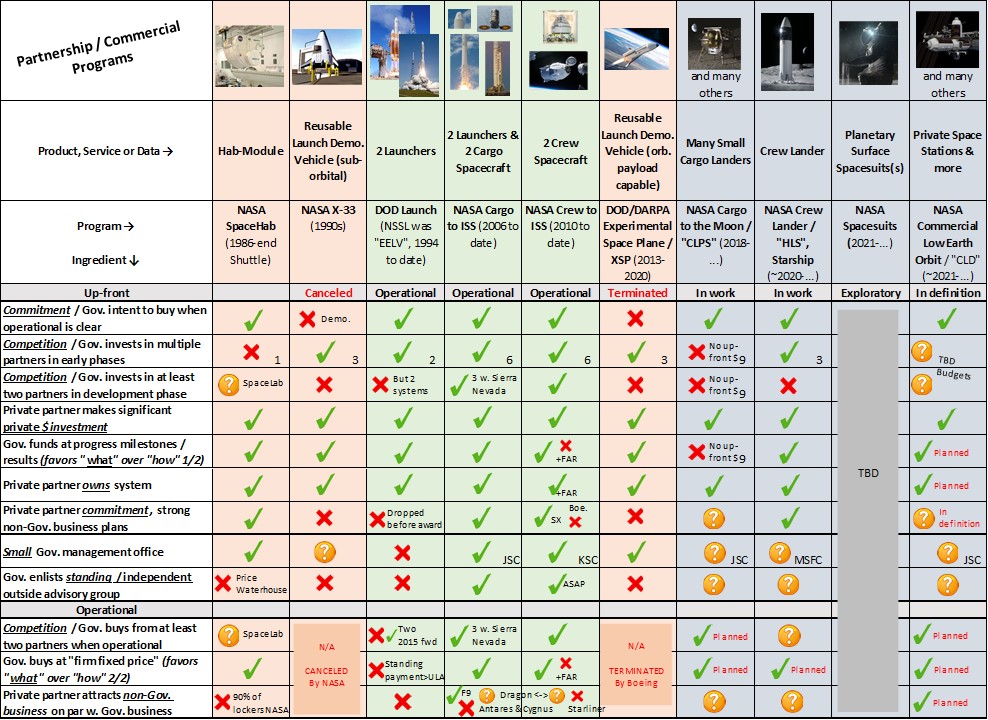

Yet is going “commercial” merely a fixed price contract or payments by milestones? Probably not. And by checking off just what is more “commercial,” we can start planning ahead with our eyes fully open. Consider these ingredients defining just what is commercial (updated since last visiting this topic):

Up-front

- Commitment – The government’s intent to buy when operational is clear

- Competition – The government invests in multiple partners in the early phases

- Competition – The government invests in at least two partners in the development phase

- The private partner makes significant private $ investment

- The government pays / funds at progress milestones/results (favors “what” over “how,” one of two)

- The private partner owns the system

- The private partner commitment is strong, with non-government business plans

- The government management office is small (relative to the scale of funds)

- The government enlists standing/independent outside advisory group

When Operational

- Competition – The government buys from at least two partners when operational

- The government buys at “firm fixed price” (favors “what” over “how,” two of two)

- The private partner attracts non-government business on par with government business

Immediately, some “X” marks draw the eye. Should NASA invest in lunar cargo capabilities up-front (the second and third ingredient for “CLPS”)? There remains much uncertainty over the funding for commercial low Earth orbit and private space stations that could be what follow the International Space Station. There is only one commercial lunar lander where it would seem successful programs (like cargo and crew to ISS) have two providers (the third ingredient for the crew lander). Does a seeming lack of government commitment to buy once operational doom any programs early on (the first ingredients for X-33 and XSP)? Or is it more likely a critical flaw leading to problems is funding just one partner up-front (common among X-33, EELV, XSP, and now the crew lander)? Or are their relationships, one flaw, not enough to spell defeat if all the other ingredients are checked off? These are questions still to figure out.

Fitzgerald may have sounded the alarm long ago about cost-plus programs. Experience tells me his two phases of a program – too early to tell and too late to stop – are not unique to cost-plus contracts. Complicated space exploration plans with many moving parts that have gone askew before are unlikely to find simple solutions when trying again. If the two project phases we want are to get results and grow demand, understanding precisely why something worked before will be as important as knowing what did not.

Also see:

- May 21, 1999, Wall Street Rejects VentureStar

- About the private investment amount in the X-33 – “Teets statement before the Senate was tantamount to admission that his company’s $230 million investment in the subscale VentureStar test craft, the X-33, would not be matched by additional billions in company funds for the full size vehicle.”

- November 29, 2018, NASA selects nine companies for commercial lunar lander program

- “NASA is providing no development money for any of the CLPS companies, who will have to raise the funding needed for their landers from other sources.”

- June 1, 2022, NASA awards spacesuit development contracts as a “service”

- “The companies will own the suits they develop and will effectively rent them to NASA for space station and Artemis missions, while also being able to offer the suits to other customers.” -this was “TBD” in the table above

- May 19, 2023, NASA selects a second lunar lander -this had only one provider in the table above, now adding competition

2 thoughts on “Revisiting commercial space and NASA”