Recently, the NASA Inspector General published another one of their periodic reports on the NASA projects that form NASA’s effort to put people on the Moon. These IG reports are always insightful, if difficult reading. More than any other NASA organization, IG auditors have access to people and information in vast, complex NASA projects – and their task is to piece it all together for public consumption. I cannot help but recall a story or two as I digested the numbers and issues and parsed phrases for meaning.

A full auditorium. The moving introduction is done with, the speeches too, something about safety and a special thank you to an employee who heroically helped on some job. As usual, it’s always a thankless, unglamorous bureaucratic task. Thank you. On to the Q&A in the last five minutes, with apologies for (as always) running over time. A fearless audience member stands up (not me) and asks a question about direction, about it being problematic for obvious reasons, suggesting how we could do better. Standing up front, the captain does not rush to take the question. As in the movies, when the troops get impertinent, the sergeant in the front row stands up instead. Let’s put this plainly. First of all, we have our orders. You don’t get to decide what we do here. This is what we have been funded to do. Simple. The sudden shift in tone bought me back on site, my brain having tuned out earlier checking texts.

Perhaps the employee that day should have led with that. Or “I have an impertinent question.”

As happens with questions, and NASA, of course, when someone says, “Maybe this is a stupid question,” they are immediately told in a pleasant, constructive voice, “There are no stupid questions.” Perhaps the employee that day should have led with that. Or “I have an impertinent question.” Instead, the stern reply said the quiet part out loud, along the lines of the teacher saying, “You, come here, right now.” Perhaps the director was having a bad day, perhaps the question could have been phrased in a manner more politic, or perhaps it was a way to say you can grumble all you want, just never in public. It may be the least memorable meeting leadership had all week. Just not to some of us straightening up in our chairs. The reply came across as scolding everyone in attendance, please listen up. (Best to quell the riot before it starts by making an example of the leader?) Or maybe, indicative of the problem, the answer confirmed the question that needed to be asked. Well, it was asked and answered.

The NASA Inspector General also asks impertinent questions. The recent questioning is especially arcane. Even for me. And I’m usually able to tell an interested reader where a number in an IG report comes from, with a spreadsheet. There are contract laws, award fees, regulations, and violations of regulations. The gist can be reduced, though – the IG says lots is amiss and problematic, then NASA replies, “You, come here, right now.”

…leadership may take the opportunity to remind the audience they are playing the cards they have been dealt.

Of course, the IG is in an excellent spot to ask tough questions more than any employee. That doesn’t mean the answers will be forthcoming. As in the auditorium that day, leadership may take the opportunity to remind the audience they are playing the cards they have been dealt. We have our orders. Next question.

NASA employees receive an email about the IG every year. It’s a reminder to cooperate fully with any IG investigation. Employees must “cooperate with OIG audits and investigations, including by providing prompt and complete access to agency information, documents and personnel.” (I always kept this email handy.)

Supporting an audit is not one of those thankless jobs for which you will one day be recognized in the auditorium. I had the good fortune to be on both sides of the table, often the independent reviewer doing the asking, and sometimes the one trying to answer the tough questions. There are auditors outside of NASA, too, like the GAO. When they come knocking, you can see projects closing the curtains and making like they are not home. No one really looks forward to these fiscal colonoscopies. It’s Monday, finally, that audit I’ve been looking forward to!

Which brings us to this day when it’s clear the lines between NASA projects and the watchers have broken down. This is not from seeing page after page about measly millions here and there. It’s not about the “$5.6M unearned balance” or the (yawn…) $28.5M in award fees NASA seemed determined to give a contractor – when the law and all evidence indicated they should not. It’s about the tone. It’s that same tone I heard that day in the auditorium. “NASA leadership was disappointed” and “did not concur” while the IG counters that NASA never provided “evidence to fundamentally change our findings and recommendations.” Hint to projects and programs – bring your spreadsheets or forever hold your peace.

But wait, if we might ask a two-part question, what with the recent Federal budget deal.

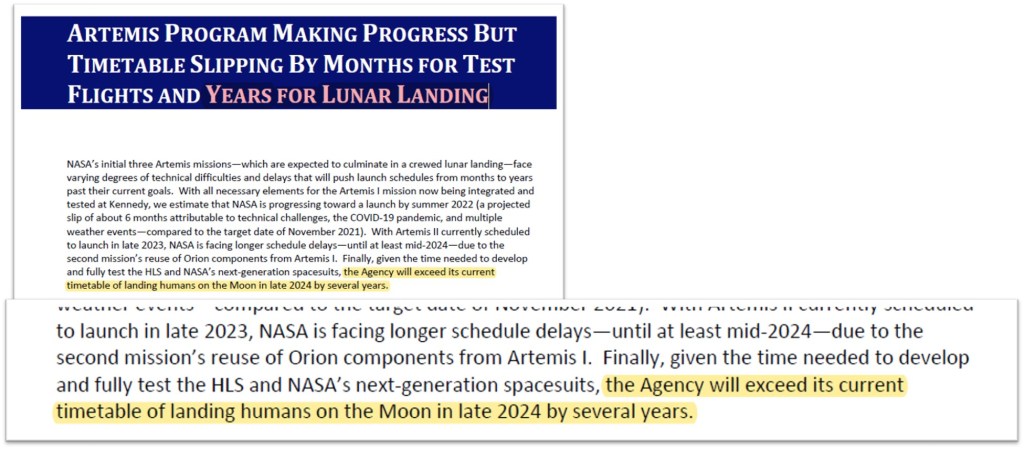

The root of this recent report lies elsewhere, back in the IG report of November 2021, receiving little fanfare at the time. Increasingly hinted at and danced around in reports stretching back years, we saw the real impertinent question. The IG concluded, “the Agency will exceed its current timetable of landing humans on the Moon in late 2024 by several years.” Alternatives are discussed, recommendations are provided. If it’s measurable, it’s good; if it’s realistic, even better.

Yet here we arrive, at IG-23-015, the fifteenth report where the NASA IG looks at NASA projects and programs in the fiscal year 2023. Fees are amiss, engines are delayed, and NASA continues to reward poor performance no one is tracking anyway. Oh, and 2025 appears more like 2028. Maybe. But wait, if we might ask a two-part question, what with the recent Federal budget deal. If things looked this poor before, what will they look like when the budget in 2024 and 2025 only goes up one percent? Or maybe the NASA budget is frozen. Might we take a look at our options?

Time for everyone to stop checking texts and pay attention.

Footnote: Advice I once heard for writers. Write like you lived it. And if you did, better.