Another day, another report by the Inspector General on NASA’s big Moon rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS.) One day, we may see a new measure for project costs and duration of development, the number of IG, GAO, CBO, or other ABC agency reports. During a coffee break, someone in the crowd will say, “That project took eighteen IG reports,” as everyone nods in sympathy, understanding the unit of measure.

Usually, I read these reports seeking strange new words, new life in old recommendations, boldly going where no one has word searched before. Then comes the parsing, splitting hairs. Like a car crash, it’s hard to turn away. But not today, as there is not much new here if you have read the prior reports. The rule proves true. Sequels are usually not as good as the original.

Even so, we have to talk. Something sticks out, as in nearly all of these reviews of complex projects mixed up in a stew of dreams and politics. Most of these reviews avoid context – the context being that NASA is looking at flat budgets ahead. But wait, if you order now, you will get more missing context – that this is no surprise.

Arthur C. Clarke once said there were three phases to a great idea:

- It’s completely impossible.

- It’s possible, but it’s not worth doing.

- I said it was a good idea all along!

What of the not-so-great ideas?

Clarke gives us one context for successful projects – the outsider’s view. Success has many fathers, but not at first. But what of the projects that run into trouble? What of the not-so-great ideas? Decades ago, Department of Defense analyst A. Ernest Fitzgerald noted two phases to an increasing number of defense projects:

- It’s too early to tell.

- It’s too late to stop.

With only these two phases, imagine trying to get your project to right its course. At which stage are assess, re-plan, and re-orient? Fitzgerald saw how projects routinely turned their start-up phases, which should be open to change based on what’s being learned, into years-long efforts reinforcing pre-mature decisions made on day one. This is not unique to the government. The private sector version is “fake it till you make it.”

Yet this digresses from context, too – why bother to stop, change course, or improve? Why bother to be real? Why drive down costs (and price) while providing a better product, faster?

In recent budget news, Federal spending for most agencies, including NASA, will be frozen for a couple of years at least. In a year with just a few percent uptick in the price of labor and goods, a freeze amounts to a slight budget cut. Now, imagine our current years with inflation running much higher. Or, without needing to do math or imagine much at all, it’s simply not if for lean budget years. It’s when. For the private sector, the end of easy money is similar, now with high interest rates. It would have helped to aim low on your project budget expectations and high on your goals for what you will accomplish. But that’s not how NASA’s (or any agency’s) project planning process works, building in ample margin for the rainy day and speeding up when skies are clear. Instead, projects plan for the best – the most unrealistic best. An old boss of mine had a saying when rumors stirred about tight times ahead, “We’ll burn that bridge when we get to it.” Obliviousness was policy.

…“research” as if the label means “likely to fail” provides a license to wander

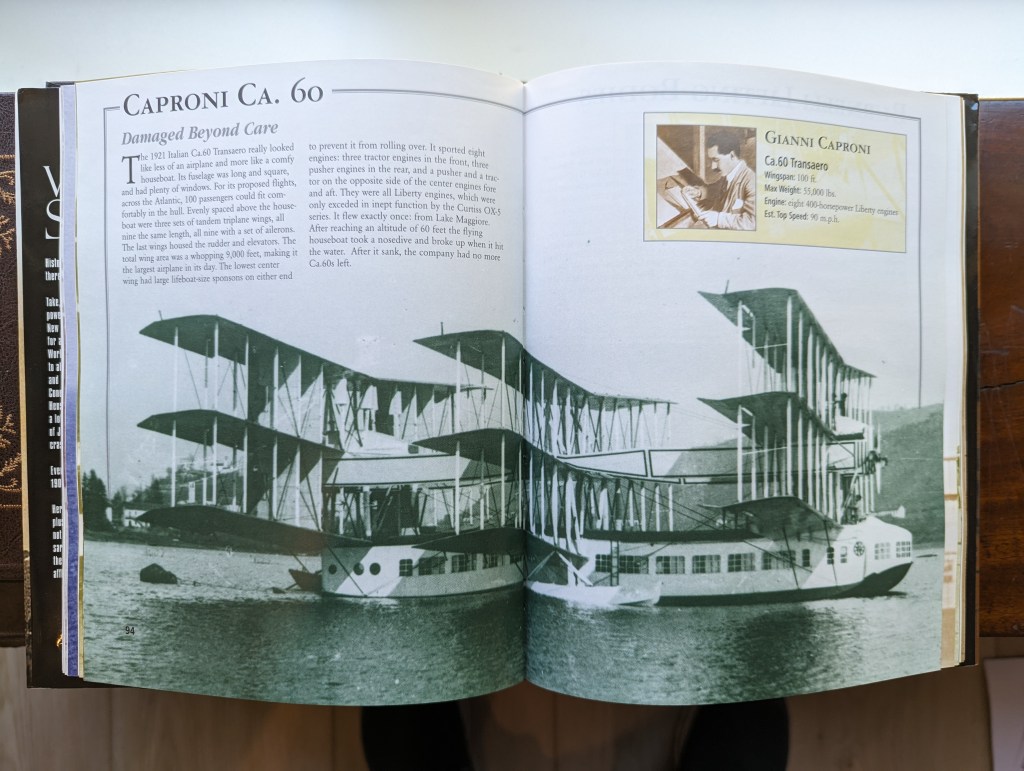

On my shelf sits a book called “The Wrong Stuff,” which tells the story of flight before (and after) the Wright brothers. “History has produced some amazing airplanes. And then there are these.” Throughout, you will find innovations that seem like they might have been on to something if, for a moment, you forget what actually worked and why flight as we know it turned out as it did. If one wing provides lift, and two provide maneuverability, then nine wings must be better.

For all the science involved, managing research and development is not yet a science itself. Most R&D fails, somewhat by definition – if we mean by R&D things that are uncertain, difficult, and beset by “extraneous variables” – the last being a useful catchall for later saying, “It wasn’t our fault.” In Pharma, 90% of clinical drug development fails. The reasons for this are not clear. The circular semantics of getting pegged under “research” as if the label means “likely to fail” provides a license to wander. This is fine when the context – your local environment – is ample funding. Throw enough darts at the board, and eventually, one of them will hit dead center. That single success may pay for all the failures. But easy money is usually the exception, not the rule.

About a year before the NASA Constellation program was canceled, the Moon program before the current Artemis version, I was asked to give a big-picture analysis of its prospects. This may have been due to a particular skill. I could connect space technology, costs, and NASA budget scenarios and translate this all into something approaching English. Or maybe I was the only one dull enough to accept the task, not realizing no one wants to discuss what they can’t control. (Remember those burnt bridges.) The scenarios were useful context – quantified. This backdrop was the focus, not the spaceships. What does the terrain look like, east or west, past the river or toward the hills? Needless to say, the prospects this first try at a Moon program would get the funding expected were less than nil. Or, more accurately, we entered the math of imaginary numbers. The program’s financial executive responded with red-faced anger, though I was told my answers to questions were Vulcan-like. (It was my turn to be oblivious.) The message came across loud and clear. The fiscal environment, ISS end-of-life decisions, inflation, and cost trends were twelve decks above my station on the Enterprise. Though my analysis proved correct a year later, this is beside the point. Judging from the lack of such context in reviews since, it appears talking points about the context programs live in remains a faux pas.

“…commercial options”

Failure is fun when we pick up valuable, critical bits from the process. I participated in failed projects, canceled, ignored, or otherwise not selected at a rate that dwarfed the successes. Perhaps we have three phases to poor ideas that also lack situational awareness – as seen by project insiders.

- Only this will work and cost the least.

- We need lots more time and money.

- You critics will get us canceled.

These phases have a common element: poor situational awareness. The final step is the most curious. Here, the news anchor Walter Cronkite is why the US lost the Vietnam War. One person, such power, to lose a war.

One day, the NASA IG or other critics may be blamed for losing the race to the Moon. Though the recent IG report includes some constructive advice on how to succeed – “NASA may want to consider whether other commercial options should be a part of its mid-to long-term plans to support its ambitious space exploration goals.” I can’t help but sympathize with the challenge in messaging, as I often provided the unwanted advice. It was constructive advice, but only if you agreed the environment ahead mattered to your limited decisions today. Of course, this is not the first IG report suggesting a course adjustment; that was twelve IG reports ago.

One thought on “NASA, space projects, and context – a missing link”