Compelling storytelling wields the power to draw us in from the first line with a curious character in a peculiar time and place. We instantly hear the voice of Harper Lee’s Scout, simple and innocent, telling us about her brother Jem. A Bradbury beginning, “It was a quiet morning,” tells us things will soon not be so quiet. “I am an Invisible man.” But why? What does that mean? We might sense the direction beforehand. This does not end well. It does not matter. We must find out how it does not end well.

Stories about technology, medicine, computers, energy, or the latest click-bait adjacent announcement about AI, neural implants, robots, or spaceflight might try and follow the format. Like a character that hooks us, a technology story pulls us in by hinting at what dreams may come. Except now, there is the challenge of not always being able to provide closure for the reader. No one knows how this will end. Where will that dream go? We are not even sure if there is a beginning.

“That won’t work.”

“Well, I agree, not now, but looking ahead, way ahead, when we think about what comes next?”

It was a typical conversation about a typical technology, not quite there yet, of course, but a candidate for NASA investment, of the sort that might one day be on the Space Shuttle or what comes after. We divided and conquered the Space Shuttle into seventy-two pieces. “Sub-systems,” we called them. The breakdown was arbitrary, and it was only long after that we realized its origins were nefarious, nothing to do with usefulness and everything to do with keeping everyone thinking inside the box. Seventy-two boxes. If the dividing was the easy part, the conquering was aspirational. If the thermal protection system dates back to materials invented in the 1970s, and here we were in 1993, it was time to think about improvements. And then on to seventy-one other sub-systems.

“Come back when that’s ready.”

“It doesn’t matter if that new thing costs less. We’re high-performance.”

“Sure, but industry’s pouring capital into this technology, not the Shuttle one, because they think one day it can have both high performance and low costs.”

“Come back when that’s ready. Also, when it weighs as little as what we have now. This is spaceflight hardware, not boilerplate stuff on a factory floor.”

This back and forth was necessary. It was an excellent way to exercise critical thinking across more disciplines than anyone would ever possess expertise. The conversation quickly deviated from how today’s technology worked to why it was around at all. Mass was usually the easy culprit to blame, the less of it being better. The designers – say “designers” as if referring to ancient heroic figures lost in myth – went with the lightest weight gizmo that packed the most punch. Want a payload on that rocket? Make everything so fragile that it breaks if you look at it sideways. This was the case with the tile for thermal protection on the Shuttles. The high-performance blurbs flowed along as another defense since we squeezed a lot of capability, whatever the case, temperature, pressure, power, speed, or all of the above, into a small package.

For me, slow to catch on, it was a while before realizing these explanations were sophomoric and a distraction from many other subtle forces at work. Sadly, the discussions did not always end well. This was a natural result of experts wanting to showcase their knowledge, confronted by my admittedly poor bedside manner, and interested more, at the time, in the problem and solution first, the patient second. The experts stood amazed with the Shuttle system they owned. I saw amazing technology overlapping with a sense of antiquity. My experience fighting fires, as we engineers said of what we did to get Shuttles fixed and ready and flying again, should have reminded me I lived in a world where the adrenaline rush was in the moment. Next year could wait.

I was not alone in trying to veer the conversations away from the harvest everyone was tending to and to the topic of selecting seeds, planting, and caring for the new field. These analogies were often atrocious, up to the point we laughed at ourselves. But they helped remind those of us looking far ahead what to focus on. Innovation. And knowing not all the seeds would sprout. Some went wide, falling on cement sidewalks.

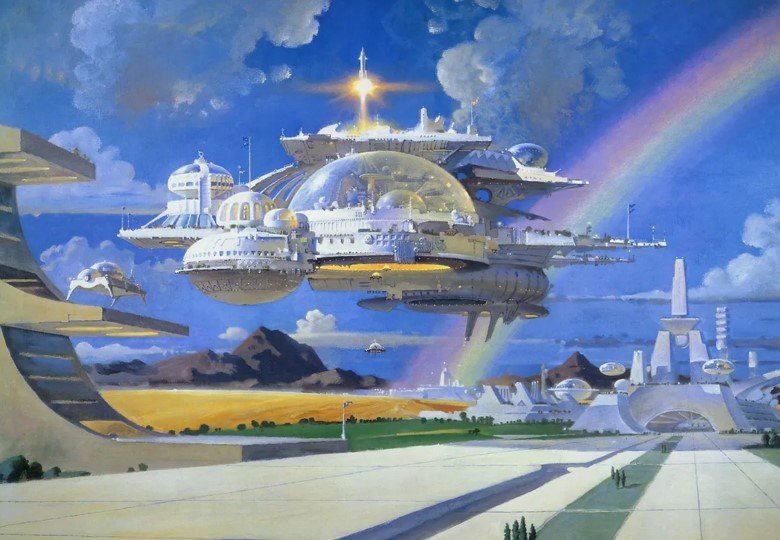

Nonetheless, we envisioned possibilities as goals. Launching to orbit as if we were on a flight to LA. Working in space as another fulfilling day, producing products essential to people’s lives. Visiting Earth, a popular travel destination with lunar citizens. But Europa gets a lot of business, too.

Soon, NASA will hold its annual NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program symposium. (It’s free to attend, in person or virtually. If you could use a yearly reminder about NASA at its best, be sure to catch it.) If you have ever seen the movie Galaxy Quest, you can visit Pasadena and meet the Thermians in person. In the film, the alien and awkward Thermians have intercepted the transmissions of an old science fiction space opera television series, a nod to Star Trek, and they believe these are “historical documents.” As Mathezar, the alien leader, says, “For years since we first received transmission of your historical documents, we have studied every facet of your missions and strategies. Our society had fallen into disarray. Our goals, our values had become scattered. But since the transmission, we have modeled every aspect of our society from your example, and it has saved us.” Inventing planet-to-orbit communicators? Check. Constructing a Spacedock? Check. Building that Starship? Check. The “beryllium sphere” to power everything? Check. Believing those sci-fi stories are historical documents does not seem a stretch – to me. Not at all. Creating cannot thrive without inspiration.

One day, it may be any one of us.

Yet new space technology, for all it might help, does not exist in a vacuum. A waiting room at a laboratory years ago. An elderly man walks in. Nearly all the chairs disappeared during the pandemic, and the room is sparse. Take away the few people and the large room says, “Available for lease.” A text system calls the person in from outside, leaving you to wait in your car until the last minute. There is an app for this. The attendant greeting arrivals from behind the glass window is also gone. Now, a shiny new kiosk stands guard beside the counter. The bright screen says, “Check in here.” A crooked sticker that seems an afterthought is above the screen, repeating this in a sizable font. The older man shows signs of losing patience waiting for an employee to appear. A groan, a mumble. Arm waving the universal sign of “Where is everybody?” I know from small talk that they now have the same people who draw blood peeking out front every so often to see if anyone needs help. Of course, someone offers to help, saying you use the kiosk to sign in. Perhaps he does not understand the machine? Then, a woman steps forward, “Your paper has a QR code on it…” Famous last words. The gentleman will have none of it. The helpful denizen is put promptly in her place, too. The lab technician finally appears after a seemingly endless, uncomfortable wait later and is also given a scolding about the lack of attention. The world changes. We can’t always keep up. One day, it may be any one of us.

A new generation of rockets came after the Shuttle. Many of the technologies we spent billions on analyzing, testing, and prototyping would finally arrive. First on our list – getting rid of nasty, toxic fluids. While we were at it, like Oliver asking for more, not to have so many different fluids and gasses, each with a supplier and nothing in common to share costs and experience with others. Today, the new United Launch Alliance Vulcan rocket employs methane instead of rocket-grade kerosene. The SpaceX Starship is doing the same, and the Blue Origin New Glenn rocket will follow with liquified natural gas (the dirtier cousin of pure methane.) Right along is electrification, using a new generation of energy-dense batteries to replace even more liquids. Today, the Electron rocket and the Starship are more electric, whereas once, a spaghetti layout of leak-prone hydraulic lines was considered the only option. The list goes on, to AETB-TUFI finally too, tough stuff compared to the original Shuttle thermal protection tiles. Not to be limited to flight hardware, newer ground systems have electric valves too, where once I was told, “Electricity and liquid oxygen, not on my watch.”

Innovations will continue in spaceflight and in our lives. Credible leaders in technology announce that a reasoning AI is a few years away. A conscious AI? A being possessing personhood, but in a box, zeros and ones and etched onto silicon or in qubits or something we can’t imagine now? If you are a certain age, perhaps like me, I am sure yet sad I will miss that one.

We know technology does not exist in a vacuum. No one knows how a particular technology will rise, like batteries, or fall, like so many airships competing against airplanes. No one knows the way the story ends for all these interesting characters. The ending, like a good story, is not the point.

Functional technology connects innovators to organizations to a tendency to say “Yes” and a desire to explore and embrace possibilities. Successful technology is not about connecting software to hardware, controllers to motors to valves. Success connects people to benefits and growth along the journey into the unknown. And not leaving anyone behind.

“In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell what a wild, and rough, and stubborn wood this was, which in my thought renews the fear!” ― Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy

Great article! Thank you Edgar, Frank

LikeLike

Thanks. Just when I think I told all the stories and made sense of them, I have to write more to figure out if I really did.

LikeLike

Please keep them coming Edgar. I really enjoy them. Have a great Labor Day weekend with your family. Frank

LikeLike

“…..experts wanting to showcase their knowledge…,” my latest mantra is “fall in love with the problem, not the solution.”

LikeLike

Ahh, yes Tracy, understanding the problem is so important. We should get to know the technology we have as if we are in love with it, it’s intricacies and nuances and history. That helps us fix, operate it and maintain the technology. Over time, though, I saw the problem was larger, as much about organizations and systems and processes as product. These are also problems we need to fall in love with!

LikeLike