Choices, a thin number, and Artemis II.

There is comfort in speaking of margins and heritage and fault trees and the clean arithmetic of it, when we can. As if numbers can absolve a choice, as if the future is a thing you can audit, and not a dark corridor you are pushed into because the calendar says go. Adding misdirection to the story, when math meets complex projects, teams talk about their problems, what broke, and the unexpected, as if it exists in a vacuum. Not the hardware that must operate in the vacuum of space. Rather, the problem. As if nothing came before to add air to the debate. What might we see, though, if we step back, as if we have been around that long and seen too much, speaking about 1967 or 1981 in the same breath as 2026?

Currently, NASA is set to launch the Orion spacecraft with a crew for the first time on Artemis II. NASA says this is supposed to happen sometime in the summer of 2026. (Does finger air-quote and rolls eyes when saying “supposed.”) This first launch with crew will also be the first complete Orion spacecraft launched, and only the second launch of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

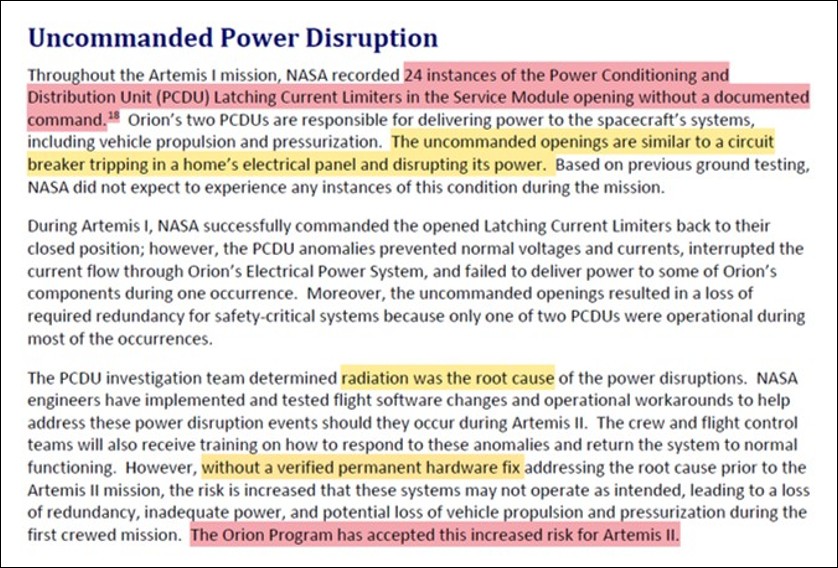

Not surprisingly, NASA’s decision to put people aboard Artemis II has been soundly criticized, at least among former NASA employees. Of course, a current NASA employee criticizing the decision would likely be an ex-employee soon after. This feature of the data points in dissent may be coupled. I have also written about Orion and Artemis II. I present the case that Artemis I, the sole Orion/SLS flight to date and a partial Orion at that, revealed enough surprises that it could not lead to the conclusion, “Now we are ready to add crew.”

I am continually amazed and enjoy how writing shows where thought gives way. What sounds whole in speech often does not stand when written. Sentences answer for one another. The chain must close. But as an engineer, training says to press on. We ask what can be counted. What can be bounded? And whether any number exists that justifies placing crew on Artemis II.

As Deming said, “Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion.” As with the 2024 Inspector General report that finally revealed the extent of Orion’s problems during Artemis I, something important is missing. This debate requires technical context. It requires reaching beyond SLS and Orion.

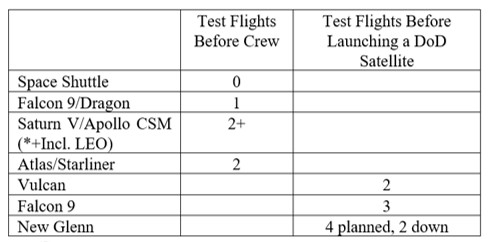

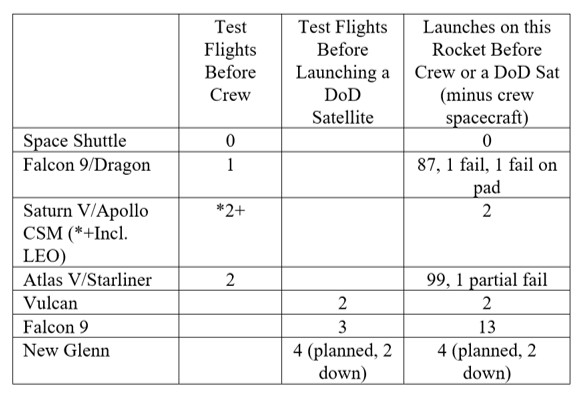

But first, a table. Some sophomoric technical context in which to place the decision to put crew aboard SLS/Orion’s 2nd flight is easy. Not technical data about Orion, or Artemis I, merely one data point, even if NASA were transparent about the flight (it is not). Instead, we can begin with a cursory look at other systems.

This initial tabulation arises, Bridge of San Luis Rey style, trying to see if there is a method to the madness. It also kicks off from any conversation with real people about NASA’s choice to launch Orion with crew for a once-around-the-Moon this coming summer. You won’t have to wait long to hear, “NASA put crew on the very first Space Shuttle launch.” This is an appeal to history, evidence, seemingly technical (true), but incomplete. It is cherry-picking data. It is one row in a sparse table. Notably, it is the first row when sorting by the number of test flights of a launcher and spacecraft before adding crew.

NASA has not had many rides to space for its astronauts, so there are not many rows. But if we bring the Space Shuttle into the conversation, we shouldn’t stop there. “Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring,” and all that. History fills in the initial table, but asks us to go further.

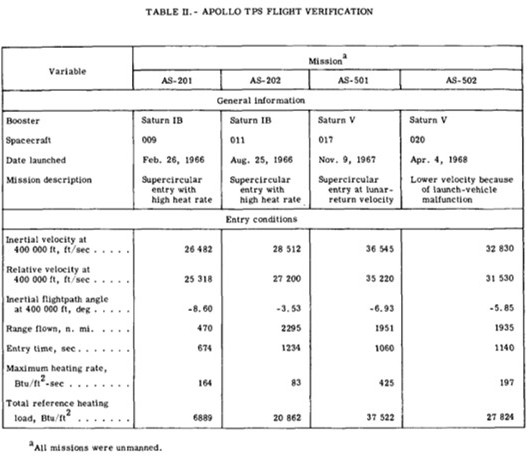

The Space Launch System and the Orion spacecraft were developed to go to the Moon, unlike the low Earth orbit Space Shuttle. As evidence gathering goes, a visit to the Saturn V rocket and the Apollo Command and Service Module must also be part of the grand tour. Time, and the entirety of the Space Shuttle generation, divides the SLS/Orion from the Saturn V and the Apollo CSM spacecraft, but scale and purpose bring them together. The Saturn V and the Apollo CSM spacecraft were launched twice (Apollo 4 and 6) before NASA put a crew aboard Apollo 8 to orbit the Moon.

Worth noting, the Apollo spacecraft also had a full shakedown cruise with a crew in low Earth orbit, Apollo 7, following the loss of crew during capsule testing on the ground. If the question is how many flights were flown on the vehicle that first sent NASA astronauts to the Moon, the answer is not two. It is three, two without crew, and one with.

Leaping ahead 52 years, SpaceX first launched a Dragon spacecraft with crew aboard a Falcon 9 rocket in 2020. Welcome back, capsules. Four years later, Boeing first launched the Starliner spacecraft with crew aboard an Atlas rocket. Dragon docked without crew at the ISS once before carrying crew. A launch abort test, Falcon 9 and spacecraft, was also part of the process of ensuring that, when crew flew aboard the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon, risks were as fully explored as possible. For the Falcon 9, there simply was not much left as far as surprises. The Falcon rocket carrying crew to the ISS for the first time did so after 87 launches. Similarly, the Starliner launched on the old-reliable Atlas V rocket, this time after two uncrewed Starliner launches to the ISS.

Yes, the one planned orbital flight test of Starliner without a crew became two. Due to near-catastrophic problems, NASA decided that a second launch without a crew would ensure that everything was truly in order. Even so, after a mostly successful second flight, significant problems still arose during the first Starliner mission with a crew, the third flight. NASA made the tough call to return the Starliner to Earth without its crew. (Left with more than enough to do at the ISS.)

Still, a data-centric view is the gift that keeps on giving. A couple of weeks ago, the Blue Origin New Glenn rocket had a second successful launch and landing, one of four leading up to certification for national security space launches. Last year, too, the United Launch Alliance Vulcan rocket completed its second successful launch, leading to certification for national security space launches in March of this year. Vulcan promptly followed up with an August 2025 launch for the US Space Force.

These two rockets, Vulcan and New Glenn, and their certification processes are a long way from 2014 when SpaceX sued the US Air Force over anti-competitive procurement practices. In subsequent years, SpaceX would be the poster child for how such a certification happens in the first place. How many successful launches are required before we trust your rocket with a high-value national security payload? For SpaceX, this would be 3 launches. Today, the US Space Force has certification options of 2, 3, 6, or 14 successful launches before taking the risk of flying with a new launcher. Apparently, a billion-dollar (or who knows how expensive, we will never know) satellite makes being picky about your rocket quite logical. One more jam-proof communications satellite, a billion dollars. Delay, bazillions more. Saving lives and winning battles in war, thanks to comms or imagery. Priceless.

If this all sounds confusing, you are paying attention. Zero launches before adding crew on a drastically new spaceship with wings in 1981. Recently, one or two successful full-up uncrewed launches at least on new systems carrying astronauts only as far as Earth orbit, with a space station in waiting, should you get in a pinch. Two uncrewed flights in Apollo, and a shakedown cruise with crew in Earth orbit, too, before a crewed launch to the Moon. A pick-a-number system, higher numbers, to carry mere hardware, not people, for the US DoD. What binds this mess together?

We are going to need a bigger table. This is not only about a spacecraft like Orion or a payload. It’s about a system. A rocket and a spaceship are necessarily a box set.

Tellingly, the Falcon 9 and Atlas V rockets had many launches before adding crew aboard a spacecraft, 87 and 99, respectively. For adding critical DoD assets, the Falcon 9 paved the way for other rockets to be certified with far fewer consecutive successful launches. Air Force personnel struggled during the Falcon 9 certification process. A job that once focused on certifying a specific next vehicle as ready to launch had to shift its mindset to certifying a design, including the processes and people that would lead to any vehicle being readied for launch.

The flash memory necessary to jump from the specific to the broad continues to plague NASA. We heard only days ago that the NASA Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel saw “confusion” during the summer of Starliner. Having suffered near-catastrophic thruster issues on the way to the ISS with the crew, the question in the aftermath was neither here nor there. Some NASA personnel thought the expected outcome was the crew’s return on the Starliner. The question for them was simple: How to do this? Others saw things differently, as in, let’s see what happened. This eventually led to a decision to return Starliner to Earth without a crew.

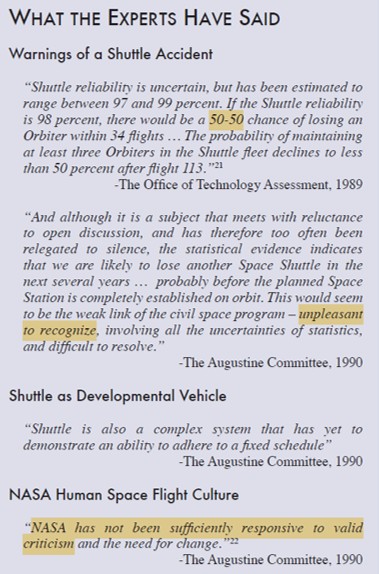

The way a question is asked decides what answers may live. Begin with the ending, and all that follows is pretense. The Space Shuttle world was built on action. Fix it. Fly it. I lived there for years, and 75 launches, and it did not tolerate doubt. Alternately, to ask only “what happened” leaves the future unbound, and that is a thing institutions fear. Imagine the answer is more testing when there is no money or time for more tests (and everyone knows this is so). Then the mind reaches for comfort. Any reasoning will serve. The preordained conclusion marries any data and any mitigations, no matter how half-hearted, and the launch proceeds. As the Rogers Committee discovered after the loss of Challenger, the word no had been reasoned out of existence.

Pause. Review. Discover. That was the proper heading in Starliner. We live too long with the faith that a person can fix anything if we only mean to. But here the figures would not bend. It was best to return the craft without its crew. They would remain above the world a while longer, happily, waiting on another ride.

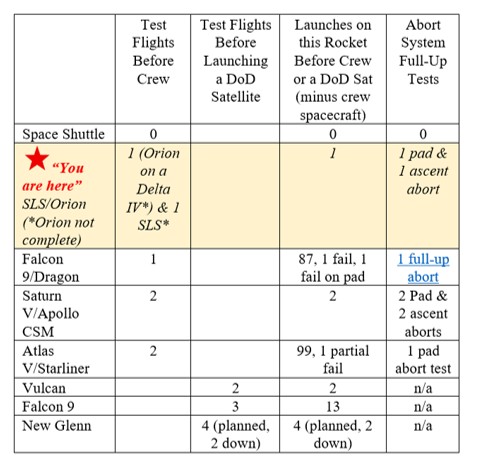

Worse could have happened. Today’s Dragon, Starliner, and Orion spacecraft have launch abort systems. Before any crew is first put aboard these systems, testing for a bad day is a given. This too must be added to the table, and now the table is nearly interesting.

We can now place the SLS/Orion decision-making about a first flight with crew in some historical, semi-technical context about testing. No one would place SLS/Orion after the Falcon 9/Dragon, which also has 1 uncrewed flight test, as it has a much longer history, with 87 launches, providing a much higher level of statistical confidence for the rocket component. SLS/Orion would also not be before the Saturn V/Apollo CSM, by current plans. Saturn/Apollo had more test flights without crew, with crew before a journey to the Moon, and more abort tests. The proper location for SLS/Orion would be in the 2nd row, right after the Space Shuttle, after those zeroes.

The landing spot for SLS/Orion on the table makes sense. A significant part of the SLS rocket is Shuttle-derived. More useful in a discussion of pedigree, the people behind SLS and Orion are NASA employees and contractors straight out of the Shuttle and ISS programs. Not that anyone else was available, after all. The same question goes for who was in the workforce at the first Space Shuttle launch in 1981? Many were NASA and contractor employees who had survived the brutal workforce drawdown post-Apollo. Here, the table is ordered by test flights without a crew, so it loses sight of the “priors,” as an engineer would say. Having begun trying to find safety in numbers, what do we see?

When lacking data of the real, nerve-racking, sphincter-contracting kind as rockets lift off, or as landing gear drops and astronauts return home, it would seem we are betrayed by small numbers. What is one mere test flight? Versus two, or three? Fortunately, the field of probability, small data sets, and gleaming insight when data is lacking has some answers.

Imagine a roulette wheel, hidden behind a curtain. You do not know how many pockets the wheel has, and worse, it may or may not have a lean to, a bias in its balance, or uneven pockets. The result of a first spin provides a “prior” as it would be called in a Bayesian view of probabilities. A single rocket and spacecraft launch is akin to the first spin of a wheel you will get to know over time. One small detail, you are told the wheel has a pocket labeled, “Lose a turn.” This is not the pocket you want the little ball to land on, ever. If spun only once, it turns out we learn something from this “prior” data point, measly as it is. If you have a good day on one spin, the chance you have another good day on the second spin is better than even. (As high as 2/3rds.) Unfortunately, this assumes you really put a lot of weight on that prior, as if the wheel, hidden as it is, is playing fair. Assume otherwise, a bit more mystery to the wheel, and you might be playing odds of as little as 1/3rd.

Confusing, but broadly saying how much store you put in that one data point decides what follows. Optimism that reads too much into one launch that does not end badly can quickly see any winning spin as paying off big, enough to buy the next launch with crew. More honestly, a launch filled with too many surprises is closer to meager winnings, insufficient to buy that next step.

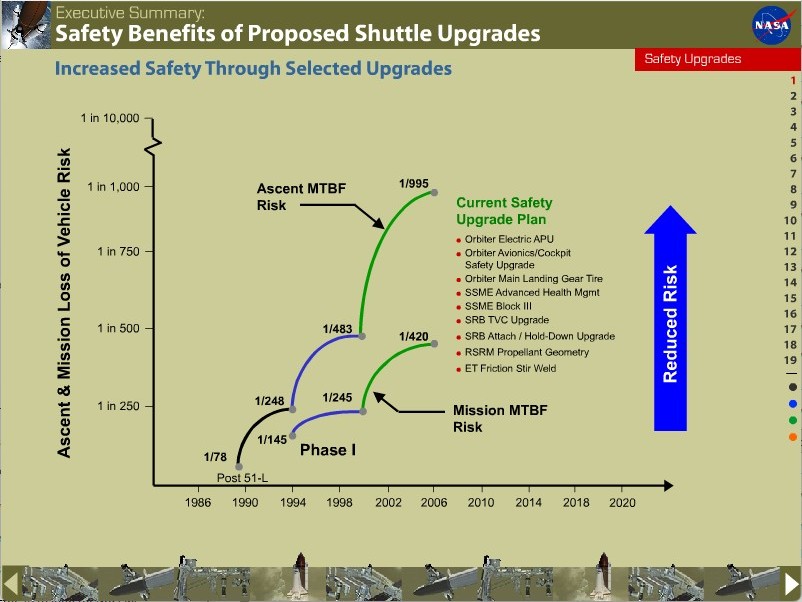

A tangible example of the mystery of reliability is documented clearly in the Shuttle program circa 2000, before the loss of Columbia. Well-intentioned NASA engineers upgrading the Shuttle and reliability analysts thought they were making the roulette wheel much larger. So many launches, so little left to surprise any of us. NASA presentations aglow about the future of the Shuttle touted an ever-improving system, approaching a chance of catastrophic failure of 1 in 245 launches. With some upgrades just around the corner, this would approach 1 in 420. At the time (the same year I left the Shuttle program), the Shuttle would have launched 100 times.

In the business of rockets and spacecraft, the roulette wheel is not only hidden at times, revealing only where the ball landed last time, it also has a history of being unfair. Apollo 13 could have ended in tragedy, and this was the 9th Saturn V and CSM launch. As the now-second committee looked at the loss of Columbia, a healthy reassessment acknowledged that the Shuttle was likely no more reliable against catastrophic failure than about 1 in 100. (Not that frank assessments around this lower number went unsaid before, overrun by the higher numbers NASA embraced.)

About now, our journey down the rabbit hole of historical context, or probabilities, for when to put a crew on a new launch vehicle may seem like a choose-your-own-adventure game. It would not be surprising if soon NASA publishes a nearly unredacted Independent Review Board report on Orion’s heat shield issues from Artemis I. This time, perhaps we also learn more about why Orion’s electrical system lit up like a Christmas tree on that one flight. The details revealed will be used to quiet this debate, while missing the point. We would still argue from thin numbers as if they were thick, as if a single flight were a verdict. Yet the basics are clear.

To put crew on the 2nd SLS/Orion flight, the first with a complete Orion, after the numerous issues encountered in Artemis I, clearly places the system, historically, near the Space Shuttle. One test flight without crew is about as close as you can approximate the Shuttle without having skipped Artemis I entirely.

Then, the SLS/Orion would be emphasized (again) as Shuttle-derived. Where specific hardware is not derived, the organization provides the prior of process, people and experience. The one data point is weighted as if it were many. The NASA team must believe this new machine recognizes them. The current SLS/Orion probabilistic risk analysis must be comforting, just as it was in the Shuttle days before Challenger and again before losing Columbia. Unsurprisingly, SLS/Orion is Shuttle-derived when it’s convenient. Why take so long, and cost so much, if it was all done before? It’s different comes the answer. The people who developed the Shuttle are long gone. Heritage is claimed or disowned as needed.

The last retorts to proper risk assessment come right along. The Shuttle Columbia launched on its maiden flight in 1981 and returned safely with its crew. There was the drama over tile, among other surprises. But all is well that ends well. This would not be the first surprise with tiles, as hundreds are again damaged years later on Atlantis. That nothing came of the debris issue at the root of this, except repair work, became cause to say nothing would happen next time, either. That corrosive logic stood until the loss of Columbia. NASA’s decision-making process converted warning sirens into silence. Starliner also returned from the ISS without a crew, without incident. You see, comes the told-you-so, NASA could have put the crew aboard after all. In each case, luck is confused with rigor and a proper understanding of risks that reaches beyond a single spin of the wheel.

In the end, it comes down to a habit. We mistake experience for proof. We ask whether this machine resembles the last one we survived. We do not ask whether it has earned the right to carry people. The machine is spoken to as if it remembers us. As if it knows who built it. It does not. Rockets remember nothing. They answer only to what has been tested and to what has not.

A launch decision’s process is not meant to ask others to prove danger. It is meant to show readiness. We have seen the façade that easily confuses the two. The process is calm. It is orderly. And it listens to the numbers only when they say “go.”