As an app, the first NASA plan to return astronauts to the Moon, twenty years ago, would have been labeled version 0.3.2.6. A year earlier, the Space Shuttle Columbia and all seven crew were lost during her return to Earth. The days of low Earth orbit as a sole destination were to draw to a close. NASA was told to finish the International Space Station, retire the Space Shuttle, and push on to the Moon and Mars. A year after this plan slash charter, NASA gathered the usual suspects (disclaimer: This included me) for a study to add specifics to our next steps. There would be three Shuttle “derived” launch vehicles, a small one for crew and two larger ones that could, one day, also get NASA astronauts to Mars. The rockets and spacecraft were new-ish enough to fit within budget projections using selective hearing about what they would improve, and only when tested on white mice. Human trials quickly proved toxic to all patients. And nineteen years to go.

If you are lost, you are not alone. Much of this would change again. Not once or a few times, but often.

The word “begat” would repeat more than in the bible if tracing events backward from today’s NASA lunar plans. A short version would start with how that 2005 study begat a program called Constellation, a short description of which might be NASA lunar program version 0.4.1.1. Buggy. Constantly crashing into reality – the reality of the Shuttle’s parts, pieces, and organizations with fixed costs and, worse, fixed ways of doing business. Like Dr. Frankenstein, some of the creators who once screamed, “It lives!” grew scared of their monster and wished Igor had never connected the lightning rod. By 2009, the villagers are seizing their torches and pitchforks (disclaimer: I constructed pitchforks) and again – change.

This is not to belittle any of these efforts. Shifts and missteps are where NASA learns, from the paths suggested in the oldest work in 2004, with Admiral Steidle, to the latest plans, the Moon to Mars (MtM) architecture, and the Artemis program. (Quick take: MtM = tools on the NASA shelves, Artemis = how NASA will use them.)

If you are confused, it means you are paying attention.

A (partially) Shuttle-derived crew vehicle. Canceled. Though practically, the booster and the capsule lived on to this day – as solid rocket boosters in the NASA Space Launch System (SLS) and as the Orion spacecraft. A short-lived attempt in 2011 to have refueling in orbit replace the SLS (disclaimer: I was part of this operation Valkyrie.) Excellent work. Not so excellent for the participants. The original lunar lander, Altair, gone before that. No lander, no Constellation program (remember the pitchforks.) A time when NASA would end the International Space Station, diverting those funds to the new programs – a short-lived delusion. Never admitting it, NASA did not even have the resources for a space station, and a new rocket and spacecraft, not as undertaken, so a lander would have to wait. About ten years of waiting. NASA awarded SpaceX a Starship lunar lander contract in 2021. And – wait for it – this lander requires refueling in Earth orbit.

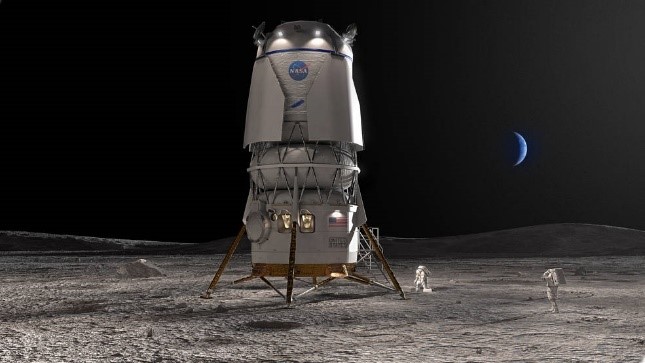

Not for lack of trying to avoid change, again, there is talk questioning how NASA gets a crew of astronauts back to the Moon. Perhaps NASA could do without a Gateway? This is one of the later “puts” not in older plans – a place where a spacecraft would drop off crew in lunar orbit before they transfer to a lander. Perhaps NASA could do without its Shuttle derived SLS. Or Orion. Or use an approach without any of the prior, if hiring a SpaceX Starship. And let’s not forget the New Glenn rocket, a big one, or the 2023 NASA award for the Blue Moon lunar lander, both by Blue Origin (disclaimer: I buy a lot on Amazon.) Or consider an upgraded Dragon spacecraft if we find Orion too expensive. All the “if-ing” here means a lot of physics, accounting, and people’s livelihoods, so jobs, and politics.

There is technology to mull over, too. For all the talk about Starship, the lander variant commissioned by NASA cannot return to Earth from lunar orbit, or from Mars if someone took a detour. For this you will need to find and collect water on the Moon (or Mars) and convert it into propellant. Then, the refueling is to gas up before lifting off with crew if they are to come back directly to Earth. Alternately, Earth orbit will do, and then a bus transfer – to an awaiting spacecraft (at the ISS?) More puts and takes might think about the steps, a Starship that stays on the Moon, one-way trips of facilities, cargo, and equipment, the kind for turning ice into propellant. It’s the later lander Starships that are reused, repeatedly refueled and hopping back and forth between the Moon and lunar orbit. From there, an awaiting spacecraft returns the crew to Earth. A Blue Moon lander would do much the same, eventually, with variations on a theme – refueling in lunar orbit from tankers that arrived from Earth.

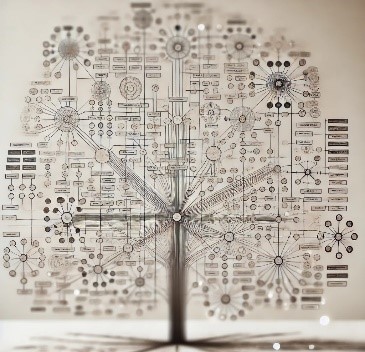

A decision tree for looking at all these puts and takes, how one element affects others, and the proper order for the possible combinations is daunting. And besides the point. The mechanical process of racking and stacking, deleting, or combining what can be combined is simple compared to the complexity of execution.

It’s been twenty years of execution and executions – what awareness might go into the debate this time?

First – terminating programs cost money. Lots of money. Not mere millions, or a year, or two, but possibly billions, and many years. Billions to stop a train, with nothing gained but a track that is cleared. Get used to it. These dollars to unwind a position must be part of any realistic “sand charts” for all the scenarios in the NASA human spaceflight multi-verse. If these dollars are missing from the analysis, someone is selling you a bridge in Brooklyn.

Second – the funds “freed up” after terminating a program will be 25-50% less than you were sold. A flaw in previous shifts came from finding out where the bodies were buried and feeling relief as if the job was done. Whew! That was hard.

This trope only works in the movies, queue exaggerated piano chords, cut to shovel, metallic sound, actor’s faces, and fade to the closing scene. In aerospace, knowing where the bodies are buried is only the start of the festivities. In NASA, the rest of the movie should be about discovering why the bodies were buried, by who, when, and how (middle act), and (final act) that now the bodies (a) were moved, or (b) were buried only to distract everyone from a far vaster and more sinister plot. The inside baseball of how this happens is well understood, but the unwritten rule at NASA centers is no one talks to the cops. (Call this “the VAB effect” – where team members insist their NASA project is never that expensive, not reeally, pronounced with a long “e,” but none of them will say where the money went either.)

Third – estimating what NEW stuff really costs must abandon all hope. Optimism is the bane of past NASA course corrections. We are the children of the people in that artfully crafted shelter eons ago who got up day after day in the cold of morning. The pessimists stayed under the warm bear skin, realistic about the brutal prospects for the day, so less apt at creating copies of themselves. We are the children of the former, the fools. The result is an undefeatable, inherited bias that dooms our decisions – making us believe things will work out with no evidence to support the statement.

One solution to optimism is margin. Assume the worst case is the best case. No, it’s not going to work out. Starship propellant calculations? Assume the worst case is the best likely, and the best case is fantasy-physics. Easily remove a piece of the current NASA lunar program? Beware. The rule of “pass the buck” means the closer a project is to final hardware, the more requirements it passed to a future hypothetical piece. This helps the piece taking shape – but not the next step. And these steps are all connected. A delta-v shortcoming in a rocket? Pass it along to the spacecraft. Short on the spacecraft? Pass it along to the lander. The magic that gets everything to add up in the last decade, the pieces in work and the future pieces, now fills a large spell book. If all this pessimism means nothing adds up – get up again, in the cold of morning…and again. And again.

Fourth – there will be a temptation to raid R&D accounts to fix one, two, and three. The fortresses are now more substantial but also smaller. NASA spaceflight personnel, the civil servants who will be around a generation, must get their hands dirty at enough times in their careers. Otherwise, the smarts to properly delegate work to the private sector will die. Yesterday’s real-world experience informing the procurement of a “service” today is soon out of touch, choosing partners that don’t deliver. In a world of limited NASA resources, and when regime change comes around, it’s the R&D, technology, and infrastructure that “disruptors” see as the lunch money to bully and steal. Instead, R&D must be preserved as a location where NASA personnel (Spaceflight and the Science half of NASA, too) remain intimate with real hardware and getting things done.

More so, the unimaginative raid never finds much gold. Return to points one, two, and three.

Fifth – while all the drama has the cell ringing and interrupting your groove, and spreadsheets and colorful charts fill the Slack channel – stop. To judge from past fire drills, all this is also beside the point.

Forget the math, the money, the SLS or Starship, old and new space, and politics (if only for a while.)

Previous iterations on what comes next for NASA focused on answers to poor questions. How to get back to the Moon. How to do so by some date. Yawn. Rinse. Repeat.

Instead, question the questions. Avoiding asking “why” NASA explores leads to repeating prior missteps.

Begin with benefits for everyone back here on Earth, and we might find sturdier ground beneath our feet. Ironically, an unimaginative shortcut to the Moon believes we must divert NASA resources from low Earth orbit. The supply chain to the Moon does not begin by breaking the link back to Earth. Economic growth in low Earth orbit will strengthen anyone’s ability to go further – to the Moon or Mars. Starlink does this for SpaceX. The ISS does this for NASA. What’s to come with NASA and private sector commercial space stations will do this for everyone. The benefits of space, from new medicines to new materials, are on the way to any sustainable activity beyond Earth’s orbit. It is not LEO “or” the Moon, “or” Mars. NASA’s “Moon to Mars (MtM)” should be the LEO to the Moon to Mars architecture (LtMtM).

The list could go on. Beware of leaders saying they are playing chess to everyone’s checkers. If you’ve seen the play before, you know it’s Magic: The Gathering. Best to think of the weather and chaos. And no one is of any matter here. But admitting to my optimism, perhaps this time, if we have learned anything, we will get closer to releasing NASA’s human spaceflight and exploration program – version 1.0.

Great Article! Frank

LikeLike