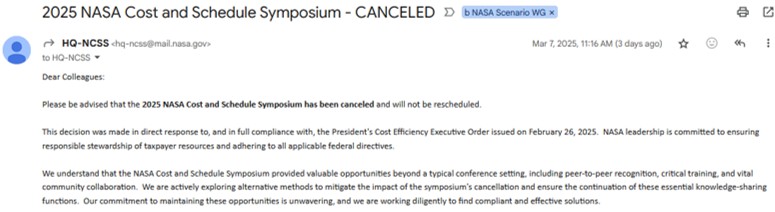

Last Friday, though without reading too much into how bad news is announced on Fridays, NASA canceled its annual cost and schedule symposium. This meeting brings together an assortment of people, mainly NASA and contractor personnel, most of whom spend their days analyzing the cost and time required of complex aerospace projects. This could be about looking back at what happened (say “what happened” with a sense a project has gone off the rails) or looking forward while a project still has plenty of runway. The former is talk therapy, trying to get at the trauma that got us in the room with the candle, while the latter is the lookout hollering about the iceberg ahead.

In whatever case, the gathering is filled with people driven by a sincere sense of wanting to understand how complex technology relates to byzantine organizational practices, meaning money moving in mysterious ways. Our sector fondly reminds everyone at any chance, “Space is hard.” Want to tackle something else as hard? Go figure out what the project will cost.

I dabbled for a couple of decades in cost estimating at NASA. Some might say I learned enough to be dangerous. Or at least to publish papers. Want to do better, end up at a new technology. Or, more insanely challenging to corral, try “new ways of doing business.” The next obvious question is, how much better? If you dare ask.

Performance improvements could answer the question, but that reply is always incomplete. Promising and valuable new technology often has little to do with better performance. A new thermal protection system tile, like the thousands used on the underside of a Space Shuttle or today on the sides of a Starship, may resist temperatures no higher than older materials. They may be slightly worse. But they may also be hardier and more resistant to damage. If you stay below the rated temperature, their life may also be longer before replacing them. They will also weigh a tad more, beginning the uphill battle for the technology to displace what came before in a world where a few pounds mean the older lightweight technology sticks around – forever.

Costing, that’s hard.

This dysfunction of favoring a few pounds more payload mass on a single flight at the expense of more flights at a lower total cost is its own problem. It’s also the kind of understanding that comes from gathering the experts who step back and look at these relationships. Materials, meet technology, and its friends, mass, and payload. And here comes demand, flight rate, and time. Costing, that’s hard.

The cancelation of the annual gathering of cost estimators is not unexpected. Estimators love to put a dot on a graph, then a second, a third, and then a line connecting the dots. (Each dot can even represent hundreds of technology and organizational choices.) There will be confidence levels, the three sigma of this, the variance of that. This is the sort of meeting where I am saddened to remember all the Calculus from college that I have forgotten.

A trend to draw through the minuscule dot that is this gathering goes through all the other dots on the graph.

A couple of decades ago, NASA counted many groups, sub-groups, boards, and teams grappling with costs and schedules. Money and time. Though, of course, time is money. Anyone getting their hands dirty with technology also had to figure out the dollars and sense of why the task at hand had value. The justification around getting funded meant really getting your hands dirty. NASA counted with an Independent Program Assessment Office (IPAO) – since eliminated, mostly. The Cost Analysis Division (CAD) at NASA Headquarters, also gone. Standing Review Boards (SRBs) in the days of NASA’s first program to return to the Moon (or the third or fourth, depending on how you count) – eliminated around 2010. The latter is especially ironic: the canceled Constellation Moon program showed staying power, as did the SLS and Orion programs, but the boards for these projects did not.

This list goes on, adding dots to the graph.

“Shooting the Messenger”

Individually, none of this would be cause for concern. Except the dots keep going up on the graph. It seems not too long ago that we saw where NASA leadership defended not structuring a program to ease accounting of what things will cost – not that they will make an extra effort to help figure it out. (The byline – “Does Congress care?”)

Naturally, there was never a lack of conversation among the survivors about the cause of a working group’s recent demise. A favorite was “Shooting the Messenger.” This explanation assumes people who deliver bad news do not endear themselves to anyone. Another theory had the last men and women standing blaming themselves, though this version took on two flavors. The saccharin version said the NASA cost estimating community saw only problems. Once, a manager added to this self-flagellation, saying he wished people would start to bring him solutions, not problems. (Some took this to heart. The reply – there is no funding for that.) The salty version said NASA has “Too many cooks in the kitchen.” The solution, perhaps part of the earlier request, involved firing the server hollering about all the tables still waiting for their food.

Soon enough, saying, “Just do it,” became fashionable, as if this phrase could magically fix projects. For a time, fewer civil servants also came into vogue, though someone must have noticed the new contractors who did the same job were more expensive. “Fake it till you make it,” met “The Secret,” hand-crafted for aerospace.

Confirmation of the death of assessment, cost, time, independent or otherwise, is seen in the recent Augustine III report. Planning, which naturally involves looking ahead at costs and time, is now pointless. “The committee heard repeatedly from NASA leaders at many levels that they felt there was little point to internal strategic planning given the heavy influence of OMB and the Congress on yearly programs and budgets.” This confirms another sense as NASA retreated from matters of cost/time as necessary – that there is no point in getting introspective when the orders have already come down from on high. This is NASA’s Gumpian-streak, where the soldiers say the task is to follow orders. The costs are the resources provided! This is not complicated. A Group Achievement Award follows.

The GAO, the IG, and many other government agencies filled with well-intentioned analysts have arrived at similar straits. Imagine you are the Inspector General pointing out high engine costs. NASA is countering with optimism (always the optimism) about prospects for savings, but NASA also admits it does not track costs. It won’t see if the savings show up.

It’s easy to imagine what the cost analysts at NASA must be wondering.

Cost, time, schedules. This can all seem beyond arid. Having trouble sleeping? Go to last year’s presentations and locate anything with the acronym “JCL” – this will cure your insomnia. (Or for a quick nap, read this paper about NASA’s commercial programs. We don’t do this to create a thrilling read.) After all, what can all this talk about NASA and something as pedestrian as money or meetings and math possibly have to do with space, the final frontier, going to the Moon or Mars, living and working in orbit, and acting on our human curiosity?

A purpose, the NASA mission of exploring and expanding human knowledge goes hand in hand with an innate sense of obligation and a duty to be diligent stewards of limited resources. The more efficient funds are spent, the more value might be achieved for people on Earth. This is the simple parlance of “what” vs. “how” in NASA circles, and they are not severable. This need to fuse technology, projects, and programs (what) with a clear view of necessary resources and time (how), especially how to always do better, will not go away. Of course, there may be a time when that need is also canceled. Then we can all stay put, back on Earth.

I love this Edgar! 😀

Harper, Lynn D. (ARC-DI)https://www.linkedin.com/in/lynn-harper-95700833/details/experience/

Strategic Integration Advisor to the International Space Station National Labhttps://www.issnationallab.org/

Strategy Lead for NASA ISS InSpace Production Applicationshttps://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/in-space-production-applications

Lead, Integrative Studies for the NASA Ames Space Portal/ Office of the Director Partnership Divisionhttps://www.nasa.gov/ames-partnerships-office-annual-report-2023/

Technical Monitor, ISS InSpace Production and Applications flight projects (supporting NRA NNJ13ZBG001Nhttps://nspires.nasaprs.com/external/solicitations/summary!init.do?solId=%7b21E0270C-BC1F-EFC4-3D87-30713B5FF373%7d&path=open and SBIR Focus Area 22https://sbir.nasa.gov/)

Make sure to put a better idea on the table when you have one — or a worse idea will be implemented.

Identify all the valuable aspects and things that are working well BEFORE identifying all the things that need to be fixed so that you don’t damage or destroy a more valuable asset in order to fix a more trivial problem.

Decision makers can’t make informed decisions if they are not informed.

LikeLike

Thanks for the positive feedback Lynn. I suppose that seeing data pile up, in projects, performance, technology advances, and in costs, or as with this news, in daily events and what’s been “canceled,” I can’t help but draw a trend.

LikeLike

Sad news Edgar, Do we know the real reason, Frank

LikeLike

Reason is likely lacking. Though reasons, that would be a short list if speculating, none good.

LikeLike

Very nice piece, Edgar. The next time I get the green light to teach the space accounting course again, this will be required reading.

Hank Alewine

Associate Professor of Accounting

College of Business

University of Alabama in Huntsville

LikeLike

Good to see you drop by Hank. By the way, when you have a chance, send me your mailing address to my email. I have something I would like to send you.

LikeLike

inspiring! 14A book review – “When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-term Capital Management”

LikeLike