Rocket launches, a possible boil water notice here in Orlando, and hospitals caring for patients with COVID are all connected. Now, it’s about liquid oxygen, but finding more connections would not be surprising, like in any system. Oddly and often in projects, “it’s a system” was an observation that arrived at the party early only to find no one ready to receive it. If later, we were told everyone was now entertaining others. Coincidentally, I worked for some years in both liquid oxygen facilities for the Space Shuttle and a systems engineering office. Now, any news day is like the cat scene in The Matrix, that feeling of déjà vu, then brace for incoming.

It’s a hot and humid Florida day, mid-morning, and worse, everyone is in heavy denim fire-retardant coveralls. Five liquid oxygen tanker trucks park neatly in reverse, one for each valve on a fill manifold to the Space Shuttle’s liquid oxygen (or “LOX”) storage facility. The drivers pressurize their tankers, opening and closing valves at the truck’s rear housing. They connect hoses, and a welcome snowy frost covers these as liquid flows in them at minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit. The sea breeze cools, a welcome if nearly imperceptible degree, from passing over the frosty lines and if you stand in just the right spot. Once the offload is complete, the drivers disconnect the hoses, and residual droplets of LOX fall to a fizzle on the cement. We will do this many times throughout the day, to fill up the storage tank and stand ready for our next launch.

I reserved saying, “We need to think about this as a single system,” for problems we could no longer afford to think about in parts.

After spending some years working on the Shuttle’s bright orange External Tank, I saw more connections. On launch day, we filled this tank with LOX (and liquid hydrogen). I started to appreciate by then – it’s all connected, all parts of a single thing.

Eventually, I found myself in the Kennedy Space Center’s “systems engineering” office. No one had a good idea at the time what the job title meant. Our discussions meandered like Russian babushka dolls, one inside another. The avionics is a system, right? Or is the system avionics plus the body flap? Eventually, an understanding came around – like the boy who cried wolf – and I reserved saying, “We need to think about this as a single system” for problems we could no longer afford to think about in parts.

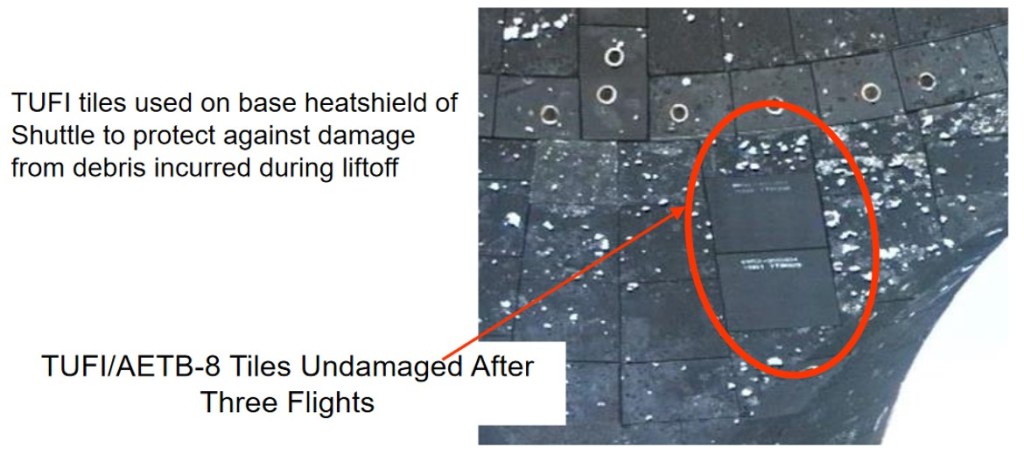

The fuselage of a reusable launch vehicle was among the first wolves we spotted. Before, it was possible to think aluminum airframe here, thermal tile over there, and lots of coordination and goo in between. However, whereas the Shuttle had an external tank, a future reusable launch vehicle, like the SpaceX Starship today, has internal tanks. Inevitably, the new arrangement of materials was now a system. You could look at it as parts here and over there but at your own peril. First is the structure (composite, aluminum, or stainless steel, as with Starship). Then, there is insulation for the super-cold liquid oxygen or methane tanks. Lastly, there is thermal protection for a fiery return from orbit, perhaps like the iconic Shuttle tiles. (And some thin layers I’m skipping over.) It is not as simple as it sounds – ponder how to stick a shower tile onto the wall insulation, not the cement board.

The “sandwich” (as I came to call it) of materials that emerged was a system. It was no longer possible to think of this bunch of items and people as pieces of a puzzle that come together at the end. The parts needed to come together at the start. The public information (below) does not do credit to the technology and its difficulties.

Unfortunately, at best, “integrating,” as we said, was a fancy phrase about making sure all these people stayed out of each other’s hair.

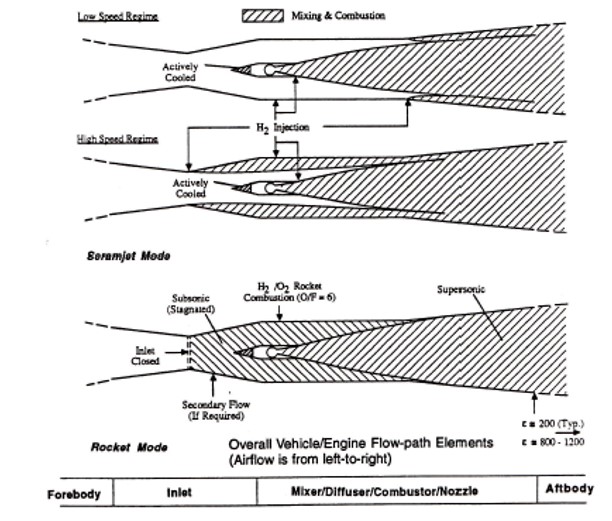

Yet, thinking of a sandwich of materials, steel, quilting, maybe foam, tiles, primers and goo and more, as a system is simple – compared to a ship you want to fly to orbit like an airplane. An airbreathing spaceplane with a hypersonic engine was another challenge for NASA and DOD projects. Again, it slowly became the consensus that it was all better viewed as a whole from the start. Breaking a problem into manageable steps or pieces is usually good until it’s not. That was the case here – unlike with a traditional rocket engine, we had connections that could not be conveniently severed to parse work. Typically, there is an engine and the ship structure, all this meaning people, with other technology and people in between. Unfortunately, at best, “integrating,” as we said, was a fancy phrase about making sure all these people stayed out of each other’s hair.

None of that will do for a true spaceplane. One day, if you were flying to orbit, like Heywood Floyd in 2001: A Space Odyssey, it wouldn’t have happened because someone broke up this new technology into smaller, more manageable pieces. This, too, will be a system, the parts all connected to where you can no longer easily say where one ends and the other begins – structure, engines, and keeping it all from turning into a molten mess.

These spaceplanes will use less liquid oxygen because, like airplanes, they will use oxygen from the air they fly through. But we must hope we don’t have a liquid hydrogen shortage one day. Again, the public information (below) does not do credit to the technology. We should build a real spaceplane someday. Hypersonics remains the part of my career where the more I learn, the less I know.

Yet technology around the corner was not the only place this happened, discovering a system where we thought we merely had a part. There are times we could have upgraded the Shuttles, only to find that changing a part affected too much else. Next-generation thermal protection tiles worked wonderfully when placed here and there on orbiters, with a world of difference from the original damage-prone tiles. But putting this new tile all over proved a leap too far, too late. The Shuttle’s parts were notoriously intertwined to the point where the tiniest change seemed to reach out and touch someone, then everyone.

Systems are everywhere, as so much is connected or should be. In these pandemic days, I see more connections we might not otherwise appreciate. Perhaps because, at the end of the day, we are all connected as well.

Well put. In fact, even the terms “systems engineering” and “systems integration” are all too-often misunderstood; or worse, used interchangeably. Back in the early development years of what ended up being called the International Space Station, I was the NASA Senior Executive in the Space Station Program Office, heading up the largest group there, which I called System Engineering and Project Integration. (The “Projects” being the 4 (initially) US Projects that made up the US part of the space station program; coupled with the IPP/International Partner Projects, of Japan, Canada, Europe, and Russia). By “largest group there”, I presented data at one point to the space station program manager, when I was begging for resources, showing that while I had over 60% of the work of the entire Space Station Program Office under me, I only had about 25% of the resources – especially only 25% of the people, who were being worked to death- to get the job done.

I was questioned sometimes about why I called the organization/work we did “System Engineering”, not “SystemsS Engineering” (or, as in the Space Shuttle Program Office, Systems Integration). I actually enjoyed explaining why I did that; because I wanted to get away from the whole idea that “all” the job we had to do involved was snapping together the individual systems that the many US and International Partner Projects were designing, testing, and building. That what we were the ‘owners’ of— and responsible for, whether the International Partners liked it or not (and some didn’t like it….but I won’t mention any group in particular…..ESA…..) what we were responsible for was the whole kit and kaboodle as a single, functioning organism. Which is why I was not only in charge of all the technical design requirements for the space station; but the functional requirements as well; e.g., dividing up power utilization, thermal utilization, space/storage allocations, crew internal time….etc.; including what turned out to be the worst one of all, EVA time needed to assemble and then maintain DURING assembly the whole thing. I finally just got to the point that, when people, askied me what my job/authority (!)/responsibility boiled down to, I finally just pointed to whatever was the overall latest picture of the whole space station was, and I’d say: “What that picture actually is, IS my job”. That usually shut them up.

Dave Huntsman

LikeLike

So true Dave. That “picture” which is how it all comes together is so much about appreciating connections rather than only parts. We neglect the picture and the connections at our own risk.

LikeLike